— Transference behaviors here meaning both ‘resistance’ in the narrow sense as well as distorted perceptions and unconscious attempts by the patient to pull us into enactments

Stepping out of the shoes and the universal wound

Nothing really therapeutic and healing happens when we are in the shoes of important but hurtful past figures — when we re-create old painful relationship dynamics with the people who come to us for help.

A nearly universal psychological wound is having been treated like an extension of another’s needs. Those lucky enough to have had such evolved parents where they didn’t have to “trim their sails to meet the prevailing winds,” where they did not have to tuck away parts of their inner life in order to not rock the boat with the caretakers — these lucky few are not as likely to need the services of a psychotherapist as the rest of us.

Even children who were victims of neglect are similarly wounded. The expectation is, “you should be OK with not having my attention. I need you not to need me.” So here too we are talking about a situation where the expectation to be an extension of the needs of the caretaker lie at the heart of the attachment trauma. And of course I am referring to prohibitions around thoughts, feelings, and desires — good parents and caretakers naturally put limits on behavior.

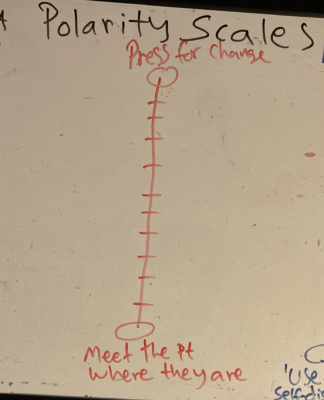

Sadly and in spite of our best intentions, ISTDP therapists appear to be uniquely prone to re-creating this trauma. When we try to get the patient to be different from the way they are before the patient has truly signaled that they really want this help; when we — again often with the best of intentions — hope to create a healing, secure attachment by continuously inviting feelings towards us before the patient has truly gotten behind that idea or can even see how it relates to their presenting problems, we are actually communicating that the patient ought to comply with and adhere to our agenda of getting the patient to be the way we think they should be. The message can become: “you should have feelings towards me. Or “you should be interested in looking at feelings towards me.”

Ironically, this recreates the universal attachment trauma and engages the very relationship rules that led to insecure, wounding relationships to begin with.

In order to truly offer a healing connection that is not tainted by the old, symptom-generating relational rules, we have to convey, not just in words but in how we are — that though we as therapists have all kinds of ideas for what will be most helpful to the patient and preferences for how to spend the therapeutic hour together, the patient is in no way, shape or form obligated to go along with or adhere to our ideas or wishes. The patient is not required to make us happy. The patient is not required to jump through our hoops or meet the milestones we hope they will meet in order to have a relationship with us.

Not only do we need to say things like the following, but we need to mean them:

— “I don’t need you to be different from the way you are”

— “You may see things differently from me, and that is OK”

— “You may not be as concerned about things that concern me, or as encouraged by things between us that encourage me. You may feel very differently than I.”

— “Here is how it looks to me, but what about you?”

— “Here is what what I envision as helping you, but you may have a different vision.”

— “I am not sure I can help you very much as long as you do X, but that doesn’t obligate you to change. I am willing to sit here with you to see if something will shift in terms of the impasse we seem to find ourselves in.”

There are clinical scenarios that require a different approach, as we for example see in Davanloo’s “BB Gun Man” (Schubmehl, 1995), and risks about engaging in a collusive alliance should also be considered. Leaving room for a ‘two-person’ relationship does not mean being a hostage of the patient. More on that in a minute.

All of this communicates: “I don’t need you to be an extension of me. There is room for you the way you are in our relationship. You are not required to please me in order to have a relationship with me.”

This way of being, by the way, is not only helpful with many of our patients, but everyone in our lives. If you supervise others, the same attitude will help you with your trainees.

Only when the patient can experience the therapist as offering that kind of relationship where there is truly room for two different people, can there be genuine healing. This applies to everyone with attachment trauma but particularly to those with a heavy load of conditional relationships where the relationship was felt to be in jeopardy unless the patient pleased the parent or caretaker and where the patient ended up being devalued and treated poorly if they did not engage the compliant, people-pleasing behavior.

Having said that, when I say “two different people,” that is what I mean. That means that you as the therapist can be upfront and transparent about your views and preferences as long as you make it clear that the patient does not need to be an extension of these ideas and preferences.

A, “Sure I would prefer it if you no longer maintain this distance and instead allow me to know the real you so we can get to the bottom of your depression, but who cares what I want? We are not here for what I want obviously, you certainly do not need to take care of me and my feelings. I can handle whatever feelings I might have about my hopes not being met. So what is it that you want? Maybe you’re OK with maintaining the distance and not getting behind your original goal — it may feel too risky to you.” Type of attitude — of course expressed sincerely and not with manipulation or devaluation, but with real respect for the patient’s right to choose is important and different from similar statements used to cast doubt on the patient’s defensive strategy.

In fact, if you try to render yourself into a blank screen without ideas and preferences, the patient will not learn to engage a two-person relationship and they are probably less likely to trust you — the patient’s problems are not your problems, but having said that, not a lot of therapists become therapists because they could care less about helping people or having good outcomes while trying to help people. Conveying indifference is not helpful.

Also, if you try to render yourself into an indifferent blank screen you’ll be a bigger target for projections — projections actually have a harder time sticking where there is a defined gestalt whereas they thrive on a blank canvas.

So you can be clear with the patient about what you see as progress impeding behaviors and you are not a hostage of the patient who has to do whatever the patient wants you to do. It simply means you are free to speak about how you see things, and the patient is free to do the same — even when, or especially when — their views differ from yours.

I am concerned about attitudes and ideas that amount to the belief that all will be well if you just add enough pressure into the patient’s system in order to activate the unconscious therapeutic alliance. I have seen clinicians that appear to subscribe to this paradigm end up dragging patients through their feelings and ultimately re-create the very relational traumas that the patient came for help with. Nothing therapeutic can happen without a genuine and strong conscious therapeutic alliance.

I never engage in serious pressures unless the patient has truly convinced me and signaled to me that they want to let go of their defenses and face what they have been avoiding. The patient needs to both consciously and unconsciously signal that they are onboard before ramping up pressure is therapeutic. This allows me to enjoy my work, not drain myself by dragging people up mountains, and I also have far better results when I do this. If you haven’t already, take a look at my video where I discuss what I call tier 1 and tier 2 for a more robust discussion on the role of pressure and the criteria for when to pressure how

Link to that video here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=39WvsvqHKsQ

On transference behavior

Everybody engages in transference. Everybody has unfinished and unresolved emotional conflicts involving genetic or important figures from our past. We all defend against facing these emotional conflicts by displacing them on to others to one degree or another.

Someone with a higher ego adaptive capacity will have the awareness or at least readily see the reality of the fact that the other person is reminding them of the person from their past, there will be an ‘as if’ quality while seeing that the other person, the therapist, is actually not the same as the past genetic figure. These people can often readily see that they are super-imposing a relational template onto the therapist and distinguish this template from the actual, non-distorted person of the therapist.

In those with a lower ego adaptive capacity, the unresolved emotional conflicts generate an anxiety that they are often not able to manage without in someway needing to distort reality. This means that these individuals, when they import unresolved emotional conflicts and past relational templates, rules, and memories onto the therapist, they will typically fail to differentiate the therapist from the past figures. This is all automatic and unconscious, by the way.

So in those who engage more regressive and primitive defenses that involve distorting reality, there will be a greater pull to engage or seduce the therapist into a kind of enactment so that the figure of the therapist will correspond to the imported and displaced material of the transference. This is to eliminate contrast between the therapist and the past figure, between the past and the present, between the reality and the fantasy. Denial is only possible when contrast is tuned out. More on that soon.

The relational dynamics that this class of patient will try to enact typically involves either mirroring the same relational dynamics that the patient experienced as a child — treating themselves as they were treated and expecting the therapist to act as the parent (or vice versa) is common, or a relational dynamic that the patient hopes will attenuate fears and sooth the patient’s concerns about a repeat of the past.

For example: “If I can seduce my therapist and have a wonderful love affair with them, then I’ll never again have to experience the kind of rejection and loneliness that was so pervasive in my childhood.”

Or, “if I can see my therapist as my father, I don’t have to face that I have murdered my father in my unconscious. …See, my father is sitting there right in front of me, I haven’t murdered him. There is no graveyard in my unconscious!’

Or, ‘if my therapist is my mother I don’t have to face that I lost my mother long ago.’

It’s the contrast between the difference between the therapist as the therapist actually is and the parent that stimulates the old unresolved emotional conflicts and intensifies the feelings towards the parents (and towards the therapist for reminding and stimulating these feelings in the patient — these feelings towards the therapist for evoking painful memories are actually not transferential, but quite commensurate with such painful reminders).

If the patient can eliminate the contrast, that normalizes the parents’ behaviors and thus helps the patient avoid the emotions about the parents. Without contrast, no emotion.

Emotions always take place where there is contrast — contrast between what we long for and the reality of what we have, between what was real and the reality of what we needed, between wanting different things that are at odds with each other, and the various configurations of these, which include the contrast between the present and the past.

This is a huge driver of the compulsion to repeat, to drag the past forward into the present to try to eliminate emotions and emotional conflicts that are activated in the face of contrast. The unconscious defensive rationale may go like this:

— “See, I haven’t lost my father, I am him/or just like him.” Or, “I am not angry with my mother, I am her.” Or, “I haven’t at some level killed off my brother, because LOOK! There he is, reincarnated in my son!”

Or, “the love I have for an (idealized) therapist will obliterate all my pain and be my salvation from any further hurts and disappointments.”

— These are all different sorts of common emotional conflicts that the transference and the repetition compulsion tries to ameliorate and paper over.

So it’s not that patients with a higher ego adaptive capacity do not engage in transference behaviors, it’s that these class of patients are less invested in denying and distorting reality. Instead, they have a greater ability to tolerate internal conflict without having to split, project, and externalize that conflict and distort reality, whereas those with a lower ego adaptive capacity will be prone to doing just that as it can be too anxiety provoking for them to face the internal conflicts that reality generates. If I can deny reality I won’t have to face my internal conflicts about reality.

If I allow myself to see my therapist as really being in my corner, that will highlight how much my parents were not in my corner and that is too much to bear for some. So the person with less psychological capacity has to find ways of seeing the therapist as not really in their corner.

I personally see this as a form of resistance but if you prefer to reserve the term resistance for a different class of patients that is fine — you can think of it as a form of unconscious transference behavior.

I have a passion for practicing ISTDP informed psychotherapy and I enjoy writing about it. For more information and what I do, visit my website: www.johanneskieding.com

I have a passion for practicing ISTDP informed psychotherapy and I enjoy writing about it. For more information and what I do, visit my website: www.johanneskieding.com